A DREAM IN HIS POCKET:

THE CRYONIC SUSPENSION OF EUGENE T. DONOVAN

This is an archived case report. It does not reflect Alcor’s current best practices for cryopreservation nor current standards for case reporting. It remains accessible for historical purposes, but, to find out more about Alcor’s current procedures, see What is Cryonics.

Cryonics, February 1990

by Cyndi Donovan, with Jim Donovan

Until recently, cryonics was something we rarely heard about and vaguely knew about. Now it’s a daily household topic. In March, 1989, my husband and I participated in the cryonic suspension of his father, Dr. Eugene T. Donovan.

My name is Cyndi Donovan. I am a 38-year-old veterinary technician. My husband, Jim, is a computer analyst. This is our story about our introduction to cryonics.

Jim’s step-mother, Dele, died in October of 1988 after a 15-year fight against breast cancer. We spent many long hours taking care of her and the last few days we were there with her 24 hours a day. She died at home with her family. Her death was hard for us, but little did we know then that our emotional ordeal was just beginning.

In September, just one month before Dele died, Jim’s father, Gene, was diagnosed as having esophageal cancer. His prognosis was six months to one year. Our first reaction was one of disbelief — then sadness — then an anger relating to, “How can we go through this again? How can this happen to us right now?” We hadn’t had time to recover from our first loss and now another one would be coming directly behind it! Dele had been cremated and buried; Jim’s father had a totally different idea for what he wanted.

Gene was 71 years old. He was a psychiatrist and was still working at the time. He appeared to take his illness in stride, although he naturally vacillated between denial, optimism, and total despair. He was also still trying to deal with the death of his wife, whom he loved more than anyone in the entire world.

Dr. Eugene Donovan in a photo taken a few months before his cryonic suspension in March of 1989. Photo courtesy Jim and Cyndi Donovan.

Jim and I both knew that Gene had always wished for immortality. He believed that science and medicine would someday provide for it but he also believed that it would never be within his personal reach.

When Gene first spoke to Jim and I about cryonics, we thought it more a passing fancy — one of his “long shots,” a denial of death or maybe he was just crazy. We didn’t know what to think! We had both heard about cryonics, but we certainly weren’t educated about it on anything more than a superficial level.

Sometime during the beginning of January, 1989, Gene told us that he’d been in contact with “this place out in California.” He’d talked with them about suspensions and they would be sending him literature. He explained as much as he could to us and said that he felt this was what he wanted. He had also contacted other cryonic facilities but was not as impressed with them. To be honest, Jim and I did not believe there was even a remote possibility that Gene would actually follow through with this — so we didn’t encourage him. In fact, there were many times when we actually tried to discourage him and would take the negative side of the issue.

Gene contacted “the place” again and again. He received literature and relayed all the information to us. We finally realized that he was serious. He gave “the place” a name: Alcor. He gave the voice on the phone a name: Mike Darwin. Jim and I began getting involved. We read everything Gene had received from Alcor and I read Ettinger’s book, The Prospect of Immortality. We both struggled with Engines of Creation, by Drexler and I’ll admit that neither one of us has yet finished it. But now we knew what cryonics was all about. If we were going to support Gene, we wanted to be informed and prepared. We still weren’t sold on the idea yet – – but we were willing to consider it as valid.

Now, Dr. Eugene T. Donovan, you must understand, is historically the world’s greatest procrastinator. If he is going to leave on a one month vacation at 9:00 A.M., you can bet money that he’ll be just starting to pack at 7:00 A.M. that same morning — and I do not exaggerate! With his failing health and his deep-seated procrastination, Jim and I knew that, if cryonic suspension turned out to be an option for him, we’d have to help. So it came as no surprise when Gene asked us if we’d talk to Mike. And, aside from needing our help, I’m sure that Gene especially wanted support and approval from Jim.

The beginning of our first conversation with Mike was loaded with pessimism on all our parts. Mike had said that Alcor doesn’t generally accept spur-of-the-moment, “I’m dying” members. He warned us that there would be a lot to do and that, even if they did accept Gene, we might not be able to get everything done in time. Then, on top of that, there’s be the added emotional aspect of a cryonic suspension.

Mike said, though, that he was impressed with Gene’s knowledge and understanding of cryonics (but not nearly, I’m sure, as impressed or awed as Gene was of Mike’s cryonic, medical, and general knowledge). Gene’s wish for suspension was not your ordinary middle of the night, death-bed request, Mike said. He was going into this with his eyes wide open and he’d thought about it for a long time so his chances of being accepted were better than most.

Gene was excited that Alcor was at least considering his request but, in turn, he was very frightened that he might get turned down. The day the phone call came to give us the “go ahead” to try and make the arrangements, Gene was like a little boy in a candy store. All of us felt good.

Now, I am your basic I-can-do-anything type person. I am also quite stubborn. If someone gives me a challenge, I jump right in. But, Mike’s cautions had impressed me. So, although I didn’t expect to fail — I wasn’t confident of succeeding, either.

Jim and I discussed everything at home that night without Gene. If Gene had any hope of doing this, we’d have to push him when he didn’t feel good — we’d have to do a lot of it in our own. But, Gene was dying. Gene wanted to be suspended and Gene needed to die with what I called a “dream in his pocket.” So we decided that night to do everything possible to make that dream come true.

All of us knew the risks and the great uncertainty — our decision was made with that knowledge in mind. If Gene did not get his immortality — he said that he’d still be satisfied to know that he might contribute, in any way he could, to advance cryonics and to allow someone else to benefit from what might be learned from his suspension.

Mike spoke of funding — we didn’t feel that would present any problem. “Paperwork,” he said — that sounded quite innocuous — so we began. Gene’s application arrived, he filled it out, we sent it back — “What’s the big deal here, Mike? We thought this would be WORK!” Then — one morning, this accurately described “mountain” of paperwork arrived. Federal Express listed it as 4+ pounds!! Mike, I will never doubt you again.

Gene was still working and was very tired most of the time. Jim and I took over everything possible. We spent long days and nights reading forms, making copies, typing, calling attorneys, doctors, and hospitals, mailing and delivering information and forms to various places, doctors, and relatives and having long talks with Gene. We replaced our telephone memo pad with a full-sized legal pad to accommodate all the incoming and outgoing information and to list all the questions we had to ask Mike on our next, almost daily, phone conversation. Mike did not lie — he did not even exaggerate about the amount of work involved! We finally set up a filing system to keep everything straight and made twice-daily lists of things to be done. Something would inevitably slip through our attempt at perfect organization — but we’d always manage to catch it later.

Dealing with the other family members turned out to be the most agonizing of all our efforts. Gene had four natural children: Diane, Gene III, Ray, and Jim. He also had three step-children from his marriage to Dele. The seven children ranged in age from 30 to 49. Gene had personally explained, but not in depth, his wish for cryonic suspension to each child and his choice for neuro-isolation and asked for their support. The oldest three natural children (Jim is the fourth and youngest) all had thoughts similar to ours at the start but they told their father that they would agree with whatever he chose to do. Once Jim and I had talked with them in more depth about cryonics and Gene’s choice, they were with us 100%. This was not to imply that they personally supported cryonics, but that they would support Gene’s decision, and they all offered to help do whatever they could. Ray even admitted that he thought the whole idea was crazy but, “if it’s what dad wants, then he should have it.” Diane and Gene III had the same feelings. All three of them readily signed and returned the Relatives’ Affidavit, but, of course their questions continued.

The Donovan children. L to R: Ray, Jim, Gene III, and Diane. Photo courtesy Jim and Cyndi Donovan.

The three step-children were a different matter. They had all told Gene that his decision was okay with them, but Jim and I immediately started hearing their complaints. Not all of them had the same objections or concerns, but this was the general overview:

They would not try to stop Gene (at first) but neither did any of them want to be involved in any way. That was fine. Jim and I respected their decisions and honesty. As Mike had told us, “cryonics is not for everyone.” Then the problems began. A valid concern was, “Who is Alcor and what qualifies them to do this?” This question, obviously, would have been better-answered by an Alcor member — but we explained the best we could. The cost of suspension became a major issue. We heard that it was a “waste,” a “rip-off,” “it’s money that should be mine after he dies.” This angered Jim and I very much. Our attitude from the start was that Gene had worked his entire life for what he had and he had the right to spend his money however he wanted. It was okay from their standpoint, for example, if he bought a sports car (we could sell it later), or even if he donated it to the American Cancer Foundation (that’s a legitimate organization) but NOT cryonics! Sadly enough, it had also been suggested by one of them that we merely pretend to Gene that he would be suspended and then to not follow through with it after his death.

A rift began in the family and Jim and I tried our best to remain open- minded, fair, and objective. We could rationalize a lot of it away as emotional stress with their mother having just died, and now Gene, but Jim and I were experiencing the same emotional stress they were. Dele had been as much of a mother to Jim as Gene was a father to them and yet their reactions were so different. The complaints mounted and we were spending precious time on the phone trying to placate them and help them understand. It took its toll on Jim and I personally because one or the other of us would be frustrated or angry at one of them, and by trying to be nice and understanding with them we’d end up taking our anger out on each other. Once we realized that this was affecting our personal relationship, we found many different ways to diffuse our anger more productively.

At one point, we were asked to stop helping Gene because everyone knew that he couldn’t succeed without us. We, of course, refused and made our position very clear to everyone — but that particular request never ceased until the paperwork was finished that gave Alcor the legal right to Gene’s remains and we were able to tell them so.

One child felt that Gene could, in fact, be crazy, and discussed having him declared mentally incompetent. Prior to that, we had discussed having Gene undergo a psychiatric evaluation to protect against just such a possibility. So we immediately scheduled the interview, which, it later gave us great pleasure to report, he passed with flying colors.

Another was embarrassed by the whole thing — “people will laugh at him — they’ll laugh at me!” We tried to explain the various reactions we had encountered from people we had told (from one extreme to the other) and said that it’s not our problem if other people can’t deal with it. It didn’t help. So we said that if they’re so concerned with what other people will think, then don’t tell them.

They had the persecution complex — “Why is he doing this to me?” We’d say that Gene was acting on his own desires and beliefs and he’s doing this to himself, not to you. Jim and I constantly felt we were being asked to take sides and, although we tried not to, Gene took priority.

Another objection was the all-out release of Alcor from any legal obligations for the suspension. “They could basically take the money and not do it and we’d have no legal recourse.” We agreed that this was a very valid point. But, Gene, Jim, and I had a “relationship” now with Mike and Alcor and we trusted them.

I guess the final big complaint was that they were upset that Gene had included their names on his initial application and that none of the step-children wanted to be, or have any of their families, connected with Alcor. We explained that Alcor provided them with that option right in the Relatives’ Affidavit — just check the proper box.

Gene had already been hospitalized once because his esophageal lesion had grown and he began choking on his food. There was talk about placing a Celestine tube or performing a gastrostomy to place a feeding tube. Gene had quit work by now and was couch-ridden most of the time. We had set up a schedule for his care and eventually, with Diane, two of the step-children, a step-niece, a close friend, and Jim and I, we had 24-hour-a-day care for him. The same hospice nurse that had cared for Dele throughout her illness now came in to care for Gene. Occasionally, we also hired an in-home nursing service.

Mike had encouraged Gene and Jim to fly to California to meet with him and see the facility. Although Gene’s health was posing a problem, they flew out on February 3rd. Mike was leaving for a one-month trip to England and he wanted Gene and Jim to meet the other staff members and establish another contact for the time he would be gone.

We had decided ahead of time that Gene would personally take his completed paperwork out to California with him and that cash up front would be the best method for payment. We arranged for a check to Alcor for the full suspension costs and on February 2nd, we set up a “paperwork” night. We hired a notary, got two witnesses, and set up an assembly line in Gene’s dining room. Gene was exhausted that night but he said not to worry about him — he’d do whatever had to be done. Two hours later, we were finished. (Two of the documents turned out to be done incorrectly so we re-executed them later and returned them to Alcor by mail.)

Gene and Jim had by now, I believe, spoken on the phone to Mike Darwin, Jerry Leaf, Hugh Hixon, and Mike Perry. But the trip to California was truly the deciding factor. They were both impressed (to make an understatement). Jim said that IF this was, in fact, a sham, it was the most elaborate one he’d ever seen and he definitely did not believe that it was. He described having the “warm fuzzies” for Alcor and its members — which translates in English to, he liked them very much and felt good about them. “These are,” he said, “very dedicated people who believe in what they’re doing.” Gene not only returned very satisfied with what he’d seen but as a full member of Alcor — complete with ID bracelet which he proudly showed to everyone.

Jim had taken notes on the facility and on each person he met so he could describe them to me when they came home. The only real judgments I could make then were that Gene and Jim believed it was good, that I liked the people I had personally spoken with over the phone, and that Jim had his “warm fuzzies” — so, we became even more determined to see it through.

On February 6th, the day after their return from California, Gene could no longer take food orally. He was admitted to the hospital and scheduled for a feeding gastronomy on February 9th. Gene was in good spirits about it and hoped it would buy him more time. Diane, Jim, and I sat together through the surgery and Gene’s recovery. He did very well and returned home a few days later, being fed a high protein, high caloric liquid diet via the gastric tube. At the hospital, they had fed him using a metered pump, but the doctors felt that Gene would do fine at home with the quicker “push feedings.” All of us learned how to feed him, but Gene basically did everything himself with just our assistance.

During Gene’s hospitalization, the step-children once again had another problem. They had all by now read the entire Relative’s Affidavit and were unhappy about being asked to send it in. “I told Gene that I’d sign a paper saying that I wouldn’t try to stop him, but I never agreed to sign something with all this other stuff in it,” one of them said.

We called Alcor and Mike told us that while they would really like to have the RAs from the step-children, it wasn’t necessary from a legal standpoint; especially since all four of the natural children’s affidavits were completed and returned. Jim and I seriously considered just telling the three of them to forget it, but we still felt it worth the effort to try to keep the family together and work it out. We felt it was important, especially now, that they be included. Once again though, valuable time was slipping away. We called a family meeting on February 12th between Jim, myself, and the step-children. All the previous problems and some new ones were discussed again and again. Since Jim had been to California he tried to relieve some of their skepticism. The effort may have been worthwhile on a personal level but we didn’t feel that we gained any ground where Gene’s beliefs or wishes were concerned. They still all agreed that they wouldn’t try to stop him. We ended up telling them to edit the Affidavits to their liking, rewrite them completely, or throw them away. But we also told them that we personally felt it was important for them to do them if for no other reason than to show Gene that they would support him.

Our only anger at any of them now is that none of them seemed to have made an honest effort to understand cryonics or how Gene really felt about it. Sure, Jim and I answered their questions the best we could, but none of them read the literature to any extent or educated themselves about it. Their opinions were emotionally based. They believe that Gene went to California to have his head cut off and frozen thinking that someday he’ll be able to come back to life. And, I agree that that’s the idea in a nutshell but it grossly negates the scientific basis, the research, and the emotions. All we ever wanted was their support for Gene — and we didn’t get it. We were able to keep a lot of these problems to ourselves, but if Gene asked, we would tell him what was happening. It would upset him a great deal, but we always assured him that none of it would interfere with his goal.

One last request was made of us from the step-children and that was that we would not actually participate in or observe the procedure in any way, not with the transport, and especially not with the suspension itself. We were asked not to go with Gene’s remains to California. Jim told them that he might not even be able to help, but if he felt he could or that he wanted to, that he would and so would I.

I guess, for me personally, Alcor still seemed a remote place that provided just voices over the phone and tons of paperwork. We seemed to be filling our time with distractions while waiting for Gene to die. We had a lot more yet to do but it still didn’t feel “real” to me. Then, in one fell swoop, Alcor was very real. Eight hundred pounds of Alcor equipment was delivered to my home. Eight hundred pounds!! It was the remote standby/transport kit. There were seven big, bright yellow boxes and one gigantic orange body transport box. Alcor had just materialized in front of me. The freight truck driver had been looking at the address labels as he unloaded the crates — Alcor Life Extension Foundation — and when he finally unloaded the body box, he jokingly asked me if this was my husband. I said “yes” as matter-of-factly as I could and you’d think the guy had seen a ghost. He said he was running late — had to go. I got quite a kick out of it.

Everyone knows that humor is a wonderful release from tension and emotional pain. As morbid as this may seem to some people, we constantly joked about Gene’s death and his upcoming suspension. Usually Gene was the best one for coming up with things to make us all laugh. When we talked about the money for the suspension, he asked if we couldn’t just stick him in our freezer and store him in our barn to save maintenance costs. From that remark, Gene III started calling him “popsicle” and we made t-shirts that said, “I love my Popsicle.” One night, Gene said that he was ready to be suspended — he was still at the time in fairly good health. Jim got up saying, “I’ll get the chainsaw.” Gene asked what he wanted a chainsaw for and when Jim replied that it was for the neuro-isolation, Gene burst out laughing. We discussed buying stock in Fridgidaire. Gene III suggested that, when he died, he would have only his body suspended — then, when the people in the future brought them back, they would put the father’s head on the son’s body and thus keep the “genes” together. Jim and I got a coffee mug that pictured a man in the winter, walking his dog. The dog and his leash were frozen solid and extending straight out into the sky. The caption read, “Greetings from colder than you can imagine, U.S.A.” . Gene told us to buy a bunch of them and send them to his family and friends this coming Christmas and sign his name to the card. The jokes went on and on and they kept us going a lot of the time.

We still hadn’t been able to coordinate a hospital and doctor yet, which, in turn, prevented us from getting a mortuary lined up, since location was of critical importance. After extensive phone calls, mailing of information, and many personal deliveries, we finally got a cooperative hospital. Then we got a doctor, but at a different hospital — no good. We couldn’t get the doctor’s hospital to approve the procedure and we hadn’t found a doctor at the other hospital to accept Gene as a patient, with his plans for suspension. We were stuck and time was running out.

Jim and I spent most of our time with Gene discussing Alcor plans and trying to get his estate in order (another time-consuming chore). I was working only part-time and Jim took a lot of time off work. If we weren’t with Gene, we were almost always doing things related to Alcor or to Gene. We came to greatly appreciate the few times we were able to sit and watch TV, or read a book, or take the dogs to the park. I guess that’s another problem that Jim and I had — the dogs. We had two — Schooner and Jesse. We had been gone a lot during Dele’s illness and we were gone even more when we were taking care of Gene. There was a lot of emotional stress and our dogs picked up on it, and, as they had done several times in the past, they began fighting. We tried everything to stop them and, with me being an animal behavior consultant at work, I mean it when I say we tried everything. On December 4, 1988, between the deaths of Jim’s parents, we had to euthanize Jesse. We both know that, given the circumstances, it was the best and only choice we had. But neither Jim or I have yet come to terms with that loss.

On February 16th, Steve Bridge flew up from Indiana to help us check our plans, to check the Alcor equipment, and to meet us and Gene and whatever other family members who would be available. We invited him to stay at our house, which worked out great because it gave us more time to get to know each other and to be further educated about cryonics. Steve met with Gene and Diane and had a chance to talk with both of them. We drove to Ann Arbor to check out locations and met with the mortician we had chosen, who was located between the two hospitals we were “negotiating” with. Steve stayed two days and left, satisfied with what he’d seen and also left us with a list of things to do.

By now, Gene’s liver was grossly enlarged — the cancer had spread not only to his liver but his bones, abdomen, and jaw. He wasn’t gaining weight; in fact, he was losing both weight and strength. He developed diarrhea and the esophageal lesion had begun to bleed a small to moderate amount. We all feared a massive hemorrhage or even heart failure. Gene had a history of heart problems, along with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (he smoked up to the day he died). He had started getting radiation therapy in hopes of reducing the size of the lesion, but it didn’t do much good. He returned to the hospital for a few days so they could regulate his feeding using a metered pump like before. This cleared up his diarrhea and he returned home a few days later. He continued to lose weight, though. We were acutely aware that a sudden death at this time would be highly detrimental to his plans for suspension — but we tried to remain optimistic. We were constantly in touch with Mike and Jerry, not only regarding the progress of our plans but about the status of Gene’s health.

By now, Mike was in England. He’d promised to come back if we needed him, but we still felt a bit lost with him gone. Jerry had taken over our phone calls and we did feel secure with him, but Gene constantly counted the days until Mike’s return. Gene also by now had a telephone unit sent out from Alcor that would dial them direct and send an emergency message in case the need arose.

Then, somehow, everything fell into place. Our hospice nurse worked out of Ann Arbor, in Washtenaw County. We had told her about our doctor/hospital dilemma (in fact we kept her up to date on everything) and she, in turn, brought it up to her supervisor. They discussed our problem at their next staff meeting, at which the Washtenaw County Medical Examiner was present. Her supervisor came up with what turned out to be a brilliant idea of which the M.E. approved. In Oakland County, where Gene lived, and where Dele had died at home, an “in-home” death involves not only a police report and confirmation from the hospice nurse and the attending physician, but also an EEG sent by an Emergency Medical Technician to a local hospital doctor — obviously a process that wastes precious time! But, in Washtenaw County, a hospice nurse may contact the attending physician to pronounce death by phone, and Alcor can take over immediately. This seemed perfect. We decided to move to Ann Arbor. We called Alcor. We called Gene’s physician and we reconfirmed the plan with our hospice nurse. Everyone said yes!

The next few days for Jim and I were consumed with phone calls and trips to Ann Arbor. We ended up with a two-bedroom “executive” apartment on a month-to-month lease (we all knew we’d probably never use up that 1st month, though). The apartment wasn’t ideal in that it was on a “garden” level, six or seven steps down from the first floor with a questionable turn at the top of the stairs for a gurney. However, the windows were large enough that we hoped we could carry Gene out when the time came if the stairs proved unnegotiable.

Gene, Jim, Diane, and I moved into the Ann Arbor apartment on March 10th, after Gene’s final doctor’s appointment. Gene immediately wanted the Alcor team to come out. Mike was now back from England and we were basically ready. The equipment and transport box were at the mortuary and not much else had to be done on our part. Jim and I were both a bit leery about calling Alcor out because it seemed too soon. Mike said it very succinctly later when he said that it’s just like Gene to procrastinate his death. But Gene’s apprehension and anxiety rubbed off on us. After all the work and effort, none of us wanted to miss the ideal circumstances for the best possible suspension. Jim called Alcor on March 11th and asked that, if it was at all possible, could someone come out now? Jerry flew in on March 12th and we all felt a lot better. By the time Jerry arrived, Gene’s other two sons, Gene III and Ray, had moved in. Mike arrived on the 15th. Eventually, there were eight of us living (and waiting) in this not very large apartment. Our hospice nurse began staying 24 hours a day on the 19th and Steve Bridge flew in on the 20th, bringing our total occupancy count to 10. Plus our dog, Schooner, whose company everyone enjoyed. I teased Mike later because, even in the midst of a heated discussion, (and everyone who knows Mike can picture him in a heated discussion) if Schooner walked by, his hand would automatically drop to pet her. As scientific evidence tells us, petting Schooner probably helped all of us keep our blood pressure and anxiety at acceptable levels.

L to R: Jerry Leaf, Ray Donovan, Diane Donovan, and Gene Donovan III, relaxing ind enjoying some coffee during the long wait at the hospice apartment in Ann Arbor, MI. Photo courtesy Jim and Cyndi Donovan.

Gene had one of the two bedrooms. We literally crammed four twin-sized beds in the other bedroom for Mike, Jerry, Ray, and Steve, and the rest of us camped out on couches, chairs, and floors. We briefly discussed getting a nearby hotel room but none of us wanted to be the ones to be away from the apartment. This might seem to have been a crowded and quite uncomfortable situation to most people, but I didn’t find it to be either. We all got along well. We all pitched in with the meals, cleaning, and caring for Gene, and even with the extra assortment of daily visitors, I didn’t feel overwhelmed. With that many people, everyone was also free to leave for a while (which we all did) and know that Gene would be in good hands. Of course, Mike and Jerry never left at the same time. Jerry even said to me that it was the most comfortable remote stand-by he’d done and he really enjoyed the good food.

As for the family, it was a time to re-establish bonds that had loosened over the years. Stories and memories were constantly being shared. For Jim and I, this was probably the most valuable aspect of Gene’s dying.

Gene had initially refused to see Gene III and Ray after his first visit with them after we had moved into the apartment. They had not kept close contact over the years and maybe Gene was resentful. He first told me and then Jim to tell them to leave. He said that they’d come to see him, fulfilled their filial duties, satisfied their morbid curiosity of seeing a dying old man and now he didn’t want them there. Neither Jim nor I could do this. We talked to Diane about it and none of us could come up with a solution. I’m not really sure how Gene III and Ray figured it out, but they knew what was going on and so we all discussed it. Jim told his brothers that it was important for them to be there for him — he wanted them to stay. Ray finally said, “I’m staying and I don’t care if he likes it or not. I just won’t go in to see him and he doesn’t even have to know that I’m here.” Gene III agreed. We all agreed because the family needed each other now — the family needed the support, the loving, and the sharing of the burden. We all felt bad that Gene felt this way but we decided it was probably more Gene’s pride that anything else. His two eldest sons had never really known Gene to be sick or weak or dependent and I suppose Gene felt embarrassed that he now needed help to do even the simplest things. Jim told his father of the decision we’d made and he agreed to let them stay “for Jim’s sake.”

I don’t know for sure what happened, but the next day, Gene called each of his oldest sons into his room and talked with them. Old wounds were healed. He accepted not only their presence but their help from then on. He told Jim and I that it was okay for them to stay now. The family was together.

By March 19th, Gene was extremely weak. He slept most of the time and talked very little. We had all discussed discontinuing his feedings as it was agreed that he was no longer benefiting from them. His doctor and hospice nurse agreed. We discontinued the pump that night and the only thing Gene received from then on was small amounts of morphine to control his pain and the Lanoxin and Verapamil he had been taking for his heart. Gene never needed much morphine — or at least he refused it most of the time because he always wanted to be able to think clearly.

Not only was Gene ready to die now, but he was frustrated (on a conscious level) that he continued to live. (Unconsciously, he was holding onto life with every ounce of strength he could muster.) He just wanted it “to be over,” he said. Gene asked several times each day about Alcor and everyone of us kept reassuring him that everything was ready. Jim finally told his father, “all we’re waiting for now is the star player.” Gene liked that. Knowing that Mike and Jerry were there and to see them every day helped relieve a lot of Gene’s fears.

If there were good things that came of Gene’s death — there was also one very bad thing that caused us all much anger and emotional turmoil. Gene was bedridden, weak and in pain. He could not recover from his cancer and he wanted to die now and there wasn’t one thing we could do to help him. We, as a society, condone and even encourage euthanasia for our pets and all other animals when all hope is gone. We consider it inhumane and sometimes illegal to allow an animal to suffer, and yet when a human being is in the same position and has the capacity to MAKE THE CHOICE we force them to die slowly and suffer terribly in the name of “precious” life. I can’t believe those people would feel the same if they had to sit at a loved one’s bedside day after day and night after night and watch that person die. I think of how easily and painlessly our dog Jesse died and it seems so unfair.

Every one of us sat with Gene. I spent many hours in his room. Sometimes we talked (about Alcor, the estate, life, death, the weather) but mostly we just sat together in silence. Or I’d sit on the bed with him and we’d just hold hands. There are two particular instances that I will never forget for as long as I live. Gene sat bolt upright in bed (not an easy feat for a dying man), looked directly at me, and asked, “Am I in California yet?” I told him that he wasn’t — he was still here with us. I reassured him again that he would go to California for sure but he just fell back onto the pillow and stared at the ceiling. Nothing I could say that day seemed to cheer him up. The day before he died, too weak to even lift his head, he opened his eyes and asked me, “Where’s my head?” I said that it was still here with us. I could see the disappointment on his face so I quickly said that it wouldn’t be long now — “you’re going to California — we’re coming down the home stretch. NOTHING CAN STOP US NOW.”

Gene smiled, ear to ear, nodded his head and gave me the OK sign with his hand. At that very moment, I really felt the full importance Gene had placed on his suspension. I had absolutely no doubt that all our hard work and exhaustive efforts were more than worth it. The memory of that smile on his face is all the reward I could ever want and I felt quite proud of myself and Jim and for everyone else who had helped prepare Gene for his last wish.

Outside Gene’s room, we had all discussed our particular roles and tried to be prepared. Mike, Jerry, and Steve busily checked and rechecked the equipment. The night of March 20th, Jerry and Steve reconstituted and mixed all the medications as the hospice nurse said that it could “happen at any time now.”

The night before. L to R: Jerry Leaf and Mike Darwin watch as Alcor Midwest Coordinator Steve Bridge draws up medications. Photo courtesy Jim and Cyndi Donovan.

The day before, we had assembled and tried out the Pizer tank which was out on its first field trip. Using Mike as our “patient,” the first problem occurred as the tank separated at the center under his weight. Mike and I made a quick trip to the store for two motorcycle tie-down straps, secured the tank posts with them and it worked fine. The second problem was, as we had feared, that it wouldn’t make the turn at the top of the stairs to go outside. Fortunately, we had plenty of manpower to lift the tank out the window. It was perfect.

Gene died at 8:19 a.m. on the morning of March 21, 1989. All of us were with him. The hospice nurse pronounced death and, from somewhere in the room, someone said, “Let’s go!” We all quickly wiped our tears and the transport began.

Jim did manual CPR while Mike and Steve hooked up the HLR. Jerry placed an endotracheal tube, I tried to place an IV catheter and Diane, Gene III, and Ray assisted all of us.

I remember sitting on the floor next to Jim and becoming frustrated at not being able to insert the catheter readily. Jim was counting compressions when I heard his voice start to tremble. He was fighting very hard not to cry. For one brief moment, I thought we’d all just fall apart. I reached up, grabbed Jim’s arm and said, “You’re okay.” He had to stop counting out loud for a few moments but he never missed a compression.

Once the HLR was in place and an airway had been established, the HLR malfunctioned. Actually, it was more a problem of securing it around Gene’s chest. Steve had brought a backup unit with him from Indiana and, with a quick change of parts, we were back in business. I, however, was still unsuccessful in placing the IV catheter.

We moved Gene from the bedroom out into the Pizer tank in the living room where Diane, Gene III, and Ray were ready with the ice. Mike now inserted a rectal thermometer and then he and Jerry pitched in to help place the catheter. Gene was so dehydrated that we just couldn’t do it.

Even though I am used to working under similar circumstances with animals, I’d never before used a 14-gauge catheter — I’m used to much smaller ones. I needed something more familiar to me. I remembered my animal emergency kit in my van, and Gene III ran out to get it. I didn’t have any IV catheters, but I did have some 22-gauge needles. Mike attached a needle to the first drug syringe and, after a couple of tries, I hit a vein and injected the drug. When we changed syringes, I lost the vein. I tried again (new needle, different vein) but, although the hit appeared to be good, the medication went perivascular. We discussed doing a cutdown but Mike said the surgery kit was at the mortuary. Fortunately, I had a scalpel blade and a pair of hemostats (the bare necessities) in my emergency kit and Jerry was able to do a nice cutdown. They administered the drugs and started IV fluids. For me, that was the most frustrating part of the transport. We had discussed inserting a catheter before Gene’s death but our hospice nurse was “uncomfortable” with the idea so we didn’t do it. In retrospect, Jim says that he would have insisted upon it.

The men from the mortuary had arrived, Gene was fully packed in ice, and his temperature was dropping. The Pizer tank with Gene in it went out the window with minor difficulty and we were on our way to the next phase of the transport.

The equipment at the mortuary had been set up the night before. Gene III (the Ice Man) and Ray had about 300 pounds of ice ready and, with Diane, they packaged it all into Ziplock bags. Preparation for the blood washout began. Our funeral director was fully co-operative. In fact, he basically just left us alone — offering his help only if we needed it.

The only mistake I can recall was one that I made. I was helping Mike mix the perfusate and I got a bit over-zealous with pouring in the sterile water and he ended up with a more dilute solution than he wanted. Mike said it was okay — what else could he say? I felt awful. Later, though, Mike told me that it really was all right because Gene had been so dehydrated that the extra fluid had probably even helped. Whew!

I prepped the surgical site for the femoral cutdown while Mike and Jerry did the final setup and scrubbed for surgery. Everyone else helped wherever they could. Jim took pictures to record the procedure in between helping, Steve took notes and monitored Gene’s temperature, and I assisted Jerry and Mike with the cutdown and washout.

Cyndi Donovan, Jerry Leaf, and Mike Darwin during the final stages of connecting Dr. Donovan to the blood pump/oxygenator for blood washout. Photo courtesy Jim and Cyndi Donovan.

At the beginning, when Jerry first isolated and incised the femoral artery, there was a clot. I think all three of us cursed at the same time because we knew what that could mean. Jerry removed one long clot of blood and we never found another one. (Another whew!)

Blood samples were taken throughout the washout; Mike collected, I recapped the tubes, and Jim and Diane labeled and prepared them for shipping to the lab. Everything went off without a hitch. All of us children agreed that the washout was extremely interesting and we were all glad to have been able to participate thus far.

Gene was placed in the transport box and everyone pitched in with packing the ice. The embalming room was scrubbed, the equipment was cleaned and repacked for shipment back to Alcor and flight reservations had been secured. We all went back to the apartment. While we had been at the mortuary, our hospice nurse had cleaned the apartment — just one of the many extra things she did for us. She was so wonderful. She was not only Gene’s nurse, but our friend — part of the family — because she had been with us for so long and helped us all through two very difficult times.

Ray and Diane immediately after bagging-up a cooler full of ice. The Zip-Loc bags filled with ice were used to refrigerate Dr. Donovan during his subsequent air shipment to Riverside, California. Photo courtesy Jim and Cyndi Donovan.

Jim, Ray, Gene III, Mike, And Jerry (not visible) close the shipping container at the mortuary prior to transport to the airport. Photo courtesy Jim and Cyndi Donovan.

Mike, Cyndi, and Jerry after the completion of blood washout at the mortuary in Ann Arbor. Photo courtesy Jim and Cyndi Donovan.

Steve got ready to return to Indiana while Mike, Jerry, Jim, and I showered and packed to return to California. Mike had extended the invitation for Jim and I to come back with them and to “watch whatever we could,” but I somehow felt that he was a bit leery of that. I hoped now that he felt more comfortable with our decision to go, as we had been of some help up to this point and hadn’t fallen apart emotionally. Neither Jim nor I were sure that we could handle the actual suspension, but we both needed to try. We knew that Alcor would complete it without us — but, we saw it as the culmination of a long endeavor we had begun more than two months prior. To wait at home for his cremains to be returned and then to bury his ashes just wouldn’t do. Gene had said that burial is a finality but freezing is a continuation — Jim and I needed to see the continuation.

Our plane left Detroit at 6 P.M. EST. We tried to relax. We thought maybe it would be a time to feel all those emotions we’d had to shut out — but, we were so exhausted and so excited that we either talked about the transport or slept.

We arrived at LAX about 8 P.M. PST. Jim and I left with Jerry and Carlos Mondragon to head for the facility, while Mike remained at the airport with Scott Greene and Simon Carter to pick up Gene.

When we arrived at Alcor, I was surprised. Jim and Gene had both told me about it after their trip in February, but their description didn’t do it justice. I did not, as Jim told me, expect to find the Mayo Clinic — but I was, in one word, impressed!

A lot of people were there busily preparing for Gene’s suspension. Introductions were made and everyone was friendly and more accepting of our presence than I had expected. Any worries I had about being not wanted or feeling like an outsider were quickly dissolved. Jim took me on a quick tour of the facility. It was much bigger and better equipped than I had expected. Jim did not really miss much in his description to me, but with my being a “medical” person it all just meant a lot more. For example, instead of “a huge room all full of equipment,” I could now see a well set- up and equipped surgery room.

Carlos took us out to get our hotel room and to buy more film before things got started.

When we returned, Jim and I were still unsure of what we were supposed to do or where to go so that we’d be out of the way. I asked Jerry — he said to go put on some scrubs and, at that moment, I knew that we’d be more than just bystanders, that we could help, because Jerry treated me the same way as he had back in Michigan. Sort of the old “get going” attitude. We clarified our positions with other people (i.e. to tell us if we got in the way) but not one person seemed to be concerned that we would be. Everyone took the time to talk with us and to explain the things they were doing. Jim and I both felt good about that.

Cyndi assists with prep of the patient: Mike Darwin indicates area to be shaved. Photo courtesy Jim and Cyndi Donovan.

I’m sure that Jerry or Mike will write about the technical aspects of Gene’s suspension at some future time so I’ll just continue with our point of view. [NOTE: Mike’s article was actually published before this one and is included below.]

Jim helped to position Gene on the surgery table, we both helped to keep him packed in ice, and Mike let me help with the surgical scrub.

The thoracic surgery was very interesting and Jerry was very patient with us and explained everything he had done. We watched Mike and Jerry drill the burrhole and Mike also led us verbally by the hand whenever we had questions or didn’t understand a procedure. We ended up not only watching but even assisting to a small degree by opening sterile supplies packs, checking ice, and generally playing gophers.

Jim and I had been mostly confident from the start that we could handle the suspension procedures. I routinely assist in veterinary surgery at my work and Jim often has helped me out — so I knew at least that the procedures wouldn’t affect us. We had talked a lot — even with Gene about maintaining emotional detachment after his death — the “it’s just a body now” sort of thing. But Jim and I began to realize that it was the emotional attachment that was more in control now. We were here for his father — the living Gene Donovan. We watched everything except for the infusion of the fluorescent dye to check the success of the perfusion. To tell the truth here, Jim and I snuck off during the long perfusion process to catch a short nap. Mike told us that the vessels that were visible through the burrhole in the skull “lit up like a Christmas tree.” When the time came for the “neuro-isolation,” Mike asked us if we were sure we wanted to be there. We both agreed that we did.

The neuro-isolation was the most satisfying part of the entire procedure. This was the specific act that Gene had focused upon to represent his goal. It’s the part he talked about (and joked about) the most. “It’s not the body that’s important,” he said, “it’s what’s up here. If they can save that, then I’ve gotten my immortality.”

Jim helped not only with the neuro-isolation but with the packing of Gene’s head into the bag and into the first cooling container. I observed and took pictures. Gene’s body was then prepared to be sent out for cremation.

Mike Darwin, Jim Donovan, and Mike Perry secure temperature probes in preparation for cooling of Dr. Donavan to dry ice temperature (-79°C). Photo courtesy Jim and Cyndi Donovan.

We were tired but we were still so caught up in the suspension that we stayed afterwards and helped with the cleanup. Mike passed me at the utility sinks as I scrubbed the surgical instruments they had used and he said, “You know, you don’t have to do that — it’s included in the invoice.” We laughed at that because we all knew that Jim and I never needed to help at all. We trusted Alcor and every one of its members that had volunteered their help that night — but for Jim and I, it was personal.

Jim Donovan napping in the Cryovita office near the end of Dr. Donovan’s perfusion. Photo courtesy Jim and Cyndi Donovan.

We returned to our hotel room but couldn’t sleep. We talked about everything that had happened and I wrote notes because we’d promised Diane, Gene III, and Ray a detailed account upon our return.

At 4:00 pm on March 23rd, we returned to Alcor to pick up Gene’s cremains. We didn’t get back to our hotel until after midnight. Mike took us out to have our pictures developed (he knew a place that wouldn’t object to the subject matter) and the three of us went out for dinner. We enjoyed that tremendously because it gave us a chance to know Mike on a more personal level. Once back at Alcor, everyone looked through the pictures we had taken and Alcor kept the duplicate set we had gotten.

At that point, they were very close to transferring Gene from the initial dry ice cooler to the neurocan to start cooling to liquid nitrogen temperature. We decided to stay. It was very interesting and even this “simple” process was well worth viewing. And, once again, we were al lowed to help. Jim assisted in the actual transfer, we watched the whole-body dewar being partially filled with liquid nitrogen, and I even got to operate the overhead winch. As before, Jim took pictures.

Jim Donovan with dewar containing Dr. Donovan immediately prior to the start of cooling to liquid nitrogen temperature (-196°C). Photo courtesy Jim and Cyndi Donovan.

Cyndi recovering from the suspension with the help of Alcor mascots Dixie and Slinky. Photo courtesy Jim and Cyndi Donovan.

We finally arrived home from California on Friday, March 24th. We felt great. Exhausted, but great.

Gene’s three stepchildren haven’t asked about our trip to California, and I don’t expect they ever will. One has requested that we never — ever mention Alcor or cryonics again in her presence. We will respect that request.

As for Diane, Gene III, and Ray, the five of us all got together after our return and we told them everything we could remember. They looked though all the pictures, asked questions and we explained everything we could to them.

They are all very glad they had the opportunity to participate in Gene’s last wish. Their only regret is that they could not accompany us to California to “finish the job.”

In the time that has passed now, we continue to have contact with Alcor. We celebrated when Mike called to tell us that Gene had reached the -196°C temperature and was placed in “permanent” (or temporary) storage.

There is still more paperwork to be done on our end (and probably a tremendous amount on theirs) but now the pressure is off. Alcor still needs medical files, pictures, and history-related items. Mike says they’re “data freaks” so we hope we can supply them with everything they want.

For safekeeping, everything in Gene’s file will be duplicated and Jim and I will store copies. Mike says we will be the first “off-site” backup facility.

For all the time we spent, all the pressure and frustration — we ended up with a grand experience and an even grander reward. We’re proud of ourselves, of Gene, and of Alcor. I know that there are many more things I forgot to tell. Just all those special people, important words and many emotions that elude me right now. But Dr. Eugene T. Donovan is now safely in cryonic suspension and whether he knows it or not, his dream is no longer stuffed safely in his pocket — it’s a full-fledged reality.

Gene bought what he referred to as his “lottery ticket.” He’s taken that one first gigantic step toward his chance for immortality.

We wish him all the Irish luck possible when the drawing comes around. We’re glad you made it, Gene!

From Cryonics, May 1989

A SUSPENSION IN DETROIT

by Mike Darwin

[NOTE: At the request of the family, the names used here were pseudonyms. The family later gave permission to use the real names, which appeared in the article above.]

Introduction

On January 8th, a few weeks before I was to leave for Europe, an information request came into Alcor from a Detroit-area physician who informed us that he was terminally ill with cancer and giving serious thought to arranging for cryonic suspension. Mike Perry took the call, and aided by a handy copy of “The Cryobiological Case for Cryonics,” he did a fine job of fielding a number of tough questions from the physician (whose name was Eugene Nalley) on the cryobiology of brains. A few days later Dr. Nalley called again to say that he had not received some follow-up information which he had requested from us. I called him back, apologized for the delay and ended up speaking to him at some length. It became apparent from our conversation that Dr. Nalley was anything but uninformed about cryonics and in fact had a long-standing interest in it and had been in touch with other cryonics groups.

He had given some consideration to making suspension arrangements, but was very up-front in stating that he just wasn’t satisfied with what he had seen to date. At the time we spoke, he said he felt he had about six months to a year to go, depending upon how he responded to radiation therapy for his esophageal malignancy.

A few days later he received the material I sent and phoned for additional details. We spent several hours on the phone together and at that point it became apparent to me that his situation was a lot graver than he thought. I got some detailed medical history from him and ran it past a couple of Alcor members who are physicians. Their verdict was essentially the same as mine: three to four months at best.

A few days after that call my beeper went off. It was Dr. Nalley. He called to say that he was bleeding esophageally and felt he was deteriorating at a much faster pace than he had anticipated. His energy level was also low and he had decided that he wanted to put his youngest son, Jim Nalley, in charge of facilitating his cryonics arrangements. Would I talk to Jim, he wanted to know? I made the call to Jim from an auto store parking lot near an exit from the 91 Freeway.

I ended up speaking not just to Jim, but also to his wife Cindy. The starting conditions of the call were not good from any standpoint. I was at a pay phone in a noisy parking lot, there were two somewhat nervous (and I believe more than a little skeptical and suspicious) people 2,000 miles away in Detroit, and it was necessary for me to be on speaker phone on their end of the call. Their attitude was completely understandable considering the circumstances.

At that point I considered this just another one of those awful, longshot, last-minute calls that never materialize into a suspension. Here I was, talking to two people who were confronted with the fact that someone they loved very much was dying, and in addition to the usual stress of such situation there was now the issue of cryonics to consider.

As Jim and Cindy can now attest, talking with Mike Darwin about suspending (or facilitating the suspension) of a relative is not for the faint of heart. I graduated from the Curtis Henderson school of cryonics salesmanship, which consists of giving the person a large, undiluted dose of ruthless honesty followed by a number of worst case scenarios and harsh disclaimers to be chased with a tiny drop of optimism. The first thing I told Jim and Cindy after laying out the basics was: “Your father/father-in-law sounds very weak to me. From his description of his condition I think he has greatly overestimated the remaining time he has and unless he responds to treatment dramatically (which in my personal opinion is unlikely) he is going to be unable to make these arrangements himself. In order for him to have any chance of putting cryonics arrangements in place it is going to take every bit of courage and stamina you can summon. This may well be the most difficult and challenging thing you have ever undertaken. If, when you understand what is going to be involved you cannot manage it, then tell me immediately and save us both a lot of grief, expense and lost time.”

I think this soliloquy impressed Jim and Cindy. I think the stream of details and information I supplied and the ready answers to their decidedly practical questions also helped. By the time that call was over, it was my impression that Jim and Cindy were “on the team.”

A Trip to California

A lot had to be done. A huge stack of Alcor paperwork had to be filled out, funding had to be arranged and, most importantly, Jim and Dr. Nalley had to come and see the Alcor facility. We wanted to be very sure that they knew what they were getting into. We had already briefed them on all the “bad” things about Alcor: the litigation with the DHS, the Dick Jones case, the Dora Kent case. Now they needed to see for themselves what was available and meet a broader cross-section of Alcor’s management.

The latter was especially important because I would be leaving for Europe in a few weeks. It was thus critical that the rapport we had built be transferred to someone else at Alcor so that communication would remain good and details such as hospital cooperation and shipment of the Alcor Remote Standby Kit could be worked out.

This was not an easy thing for me to do. Dr. Nalley and I had built a relationship which involved a certain amount of bonding. He trusted me, and I cared a great deal about him. He was a good, sincere, and intelligent man who obviously wanted to stay alive very much. I admire that. What I admired even more was his courage. Just three months earlier he had lost his wife (whom I could tell he dearly loved) to a long battle with cancer. He had been unsuccessful in persuading her to opt for suspension. He was 71 years old, in failing health, and none of his children had expressed much interest in cryonics either. As he said to me during one of those first phone calls, “It looks like I am going to be going into the future alone, but I still want to do it. I just don’t see any other course of action that makes any sense at all.” Spoken like a true cryonicist.

Setting Up

Jerry Leaf agreed to take over for me as the “primary” and on Friday, February 3rd, Jim and Dr. Nalley flew out to Southern California to look things over and meet with Jerry and me. Dr. Nalley was weak enough by this time that he needed a wheelchair to be taken through the facility (although he could stand and walk short distances). As soon as I saw him I revised his estimated survival time downward considerably. He had lost over 60 pounds and was markedly emaciated.

Jim and Dr. Nalley were satisfied (perhaps even impressed) with what they saw at Alcor, they had completed the paperwork sent to them a few days before (breaking the record formerly held by Dave Pizer for fastest Alcor sign-up) and Dr. Nalley was issued a bracelet and suspension coverage at the end of the tour. They flew out of Ontario Airport and back to Detroit the next day. I left for Europe the following Tuesday.

While I was in Europe, a constant worry was that Dr. Nalley would not survive long enough for me to get back. I had promised him that I would cut short my trip to come back at a moment’s notice, and he promised me he would try to hang on till I got back.

He kept his promise, so fortunately I didn’t have to keep mine. I had been back only a few days when the call came in. Dr. Nalley’s quality of life was very poor. He had not responded to radiation therapy nor had he gained any weight after a feeding gastrostomy (opening made through the stomach and abdominal walls to facilitate tube feeding) had been made and tube feeding started. His weight was down to 126 pounds from a pre-illness average of 250. He was bedfast, in considerable discomfort, and “wanted to get it over with.” In conjunction with his physician, his hospice nurse, and his children he had decided to refuse further tube feeding and go ischemic. We would be called to fly out and stand by when his condition warranted it.

While I was in Europe, Jerry Leaf and Jim Nalley had done a magnificent job of planning. An apartment had been rented in Ann Arbor, in Washentaw County, and Dr. Nalley was to be moved there when it became apparent that he would require nursing care and was in imminent danger of death. This was done because Washentaw County has an excellent hospice program and allows the hospice Registered Nurse to pronounce death in the home without the physical presence of the attending physician being required at the moment of death. A hospice service with 24-nursing personnel was selected, the arrangements were cleared with the local coroner’s office, and a cooperating mortuary with a good-sized prep room was located a few blocks away.

Another important contribution to readiness was made by Alcor member Dave Pizer, of Phoenix, Arizona. One of the things which the previous few suspensions had made obvious was the inefficiency of ice bags as a heat exchange medium. The plastic bags do a nice job of containing the ice, but they also act to dramatically decrease its heat removal capability. Not only does the plastic act as an insulating layer, it prevents the ice-cold water generated from the melting ice from flowing over the patient and carrying away heat. What is ideally needed is an ice slush bath, something that would simulate cold-water drowning, where very high rates of heat removal are known to be both possible and cerebroprotective. Ice in plastic bags simply cannot deliver the kind of heat removing capacity that ice in direct contact with the patient can or that an ice water bath can deliver.

The Pizer Tank

The problem with using such a “direct contact” scheme or an ice water bath is obvious: the mess. The only advantage to ice bags is that they keep water and ice off the floor (with varying degrees of success). What would be needed if we were to use a direct contact approach would be some kind of tub or tank which the patient could be placed in. Additional requirements would be that such a tank would have to be affordable, lightweight and above all portable.

This is where Dave Pizer entered the picture. Among other businesses, Dave and his wife Trudy own and operate a chain of auto upholstery shops in Phoenix. Dave has done a tremendous amount to help Alcor in the past both in terms of time and money, and he had previously volunteered to do any custom upholstery we needed. It didn’t seem like a service Alcor was likely to be needing at the time it was made, but then along came the idea of the “portable ice river,” as Steve Harris calls it.

Dave seemed the man for the job. He didn’t disappoint us. I rang him up, told him briefly what was needed, and followed up with a sketch which was sent off a day or two before I left for Europe. When I returned I learned that he had built the tank from the drawing and sent it along a week or so after I’d left.

The Pizer Tank, as it is called, is a 6’2″ long (inside) framework of 1- 1/4″ PVC pipe to which a flexible Naugahyde tank is attached with snaps. The tank as executed by Dave is nearly ideal: it is inexpensive, breaks down into easy-to-transport components, is extremely rugged, and can hold a full load of 75 gallons of water without leaking or disintegrating.

Nimodipine

Another change in technique used in Dr. Nalley’s transport was the substitution of the new calcium channel blocker Nimodipine for Verapamil, which we have previously used. Nimodipine has been shown to be far more effective in a variety of animal models in protecting against reperfusion injury following extended periods of cerebral ischemia. One investigator has recovered pig-tailed monkeys from up to 17 minutes of total cerebral ischemia using Nimodipine administered starting five minutes after the animals were resuscitated. The use of Nimodipine in cryonic suspension patients was not straightforward. It took several weeks of on-again, off- again effort just to develop a vehicle solution that the drug would dissolve in. Nimodipine is also very photosensitive and degrades rapidly when exposed to white light. Thus it must be packaged and delivered in photosafe vials and administration equipment. All of these problems were overcome: the last of them only a few days before Jerry and I left for Detroit.

Stand-By Starts

On March 11th, Jim called and informed us that his father was starting to slip badly and had requested that we come. Jerry flew out the following morning. After some consultation it was decided that I should keep my speaking engagement at the California Coroner’s Convention the morning of the 15th and then fly directly from Sacramento to Detroit. Jerry Leaf arrived on the morn- ing of the 12th.

If Dr. Nalley had proven too optimistic about how long he had to live, he proved equally pessimistic about quickly he would “die.” Death from dehydration is a slow, unpleasant process.

The only bright spot was that Dr. Nalley was surrounded day and night by all four of his biological children (and visited frequently by his step- children) throughout the ordeal. Jerry and I have never observed such love and care on the part of all the children in a family. They were there with him through almost every minute of what was, to put it mildly, a painful and stressful experience.

Jerry and I spent six days with the Nalley family in very close quarters. It was an enriching experience for us and one we are very grateful to have had. They are extraordinary people, each and every one of them. Just how extraordinary we were soon to find out.

Ischemic Coma

On March 19th, it became apparent to everyone that Dr. Nalley was in the final 48 hours of his illness. He was severely dehydrated and had an overlying case of pneumonia. Steve Bridge, Alcor’s Midwest Coordinator, was summoned from Indianapolis to serve as an extra hand. A few weeks earlier Steve had flown up to Detroit to meet with the Nalley family and to act as our eyes and ears in checking out the mortuary and the Remote Standby kit to make sure that everything was in order.

Jerry Leaf supervises Steve Bridge as he draws up transport medications a few hours before Dr. Nalley experienced cardiac arrest. Photo courtesy Jim and Cindy Nalley.

On the night of the 20th, Dr. Nalley’s breathing became very labored and it was apparent that he was at most a few hours from cardiac arrest. We spent a rocky night, sleeping fitfully with several false alarms. Around 8:00 AM CST on the morning of the 21st, the hospice nurse notified us that he was frankly agonal and that he would arrest at any minute. We got out of bed and began readying the resuscitation equipment and medications. We did not have long to wait this time. At 8:19 AM Dr. Nalley experienced respiratory and cardiac arrest and was pronounced legally dead by the attending nurse. At 8:25 AM CPR was begun by Jim, followed by support with a Brunswick heart-lung resuscitator.

Transport

Then the first, and thankfully the last, major problem occurred: We had requested that a “heparin-loc” intravenous catheter be put in place in Dr. Nalley while he was still alive. The hospice nurse was not comfortable with this request and gently refused it. Even though Dr. Nalley had excellent peripheral veins we were concerned about our ability to insert an IV catheter if he was badly dehydrated. As it turned out, our worries were justified. Despite vigorous efforts by myself, Jerry Leaf and Cindy Nalley (who is an expert at sticking small vessels in dehydrated animals: she is a veterinary medical technician) we could not get a catheter in. After a number of frustrating minutes of failure we decided to move Dr. Nalley from the back bedroom where he had arrested into the living room where we had our Pizer tank set up and considerably more room to work. Once he was positioned in the Pizer tank we managed to do a cut-down and start our IV medications at 8:57 AM. Luckily, Cindy had her animal emergency kit in her car and we were able to fashion a makeshift cut-down tray on the scene. We have since modified the Alcor medications kit such that it contains a field cut-down kit so that we are never in that situation again.

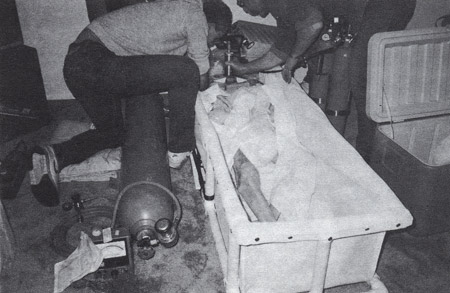

Shortly after cardiac arrest, Dr. Nalley was placed in the Pizer Tank on heart-lung resuscitator (HLR) support and external cooling with a crushed ice bath was begun. Dr. Nalley’s son Gene stabilizes the plunger on the HLR as mIke Darwin re-adjusts the securing strap. Photo courtesy Jim and Cindy Nalley.

In order to avoid splashes from the ice bath wetting the HLR backboard (which contains the pneumatic computer and monitoring gauges), a “dummy” backboard was used under the patient and the backboard containing the pneumatic “driver” was placed atop the patient where it would remain dry. Photo courtesy Jim and Cindy Nalley.

Since the stairway leading out of the building would not accommodate the Pizer Tank, the tank and patient are lifted through a windwo fo the hospice apartment. Photo courtesy Jim and Cindy Nalley.

Once he was in the Pizer tank, Dr. Nalley began to cool rapidly. In fact, his rate of temperature descent during external cooling was roughly twice that of the last patient Alcor suspended under similar conditions (Alice Black, see Cryonics November 1988). By 11:30 AM his esophageal temperature was down to 24.5°C from a post-arrest temperature of 39.5°C at 8:55 AM. This works out to an average cooling rate of 6.4°C per hour. With further refinements such as the use of a battery-operated pump and a sump reservoir of ice water we think we can increase the rate of core cooling using such a bath to 10°C to 12°C per hour in selected patients (i.e., those who are thin or wasted secondary to disease and who thus have little insulating fat and low body mass).

Another complicating factor which was beyond our control was Dr. Nalley’s low blood volume due to dehydration. Even after administering nearly 1,500 cc of various transport medications he was still severely dehydrated and probably had an even lower than the average (inadequate) blood pressure while on CPR support. The ability to rapidly cool such patients thus becomes paramount since CPR is probably doing little to meet their metabolic needs and is probably useful primarily to circulate transport medications and prevent blood from clotting.

Jerry Leaf prepares the field perfusion circuit in a mortuary near the hospice in Ann Arbor, Michigan. The dual-headed blood pump is in the foreground, 0.2 micron sterilizing filter is in Jerry’s left hand, the oxygenator is in the background obscured from vie by the sterile-wrapped A-V loop (used to connect the patient to the blood pump). The bottles contain perfusate (TPS). Photo courtesy Jim and Cindy Nalley.

Once in the mortuary, the rigid frame of the Pizer Tank was unsnapped and the patient was transferred to the embalming table for blood substitution with tissue preservative solution (TPS). Photo courtesy Jim and Cindy Nalley.

Overview of extracorporeal circuit and patient in the prep room of the mortuary. Photo courtesy Jim and Cindy Nalley.

By 11:33 AM blood washout and perfusion of the tissue preservative solution (TPS) had begun. Perfusion was effective at rapidly reducing his core temperature; dropping it from 23.5°C to 3.5°C in 45 minutes.

Despite the probable poor cardiac output from the HLR, an arterial pulse with pressure was noted during cannulation and the first venous pH was 7.16, indicating that the THAM buffer had been circulated.

Blood washout went very well. At first, we were apprehensive that we had a serious problem, since when Jerry Leaf opened Dr. Nalley’s femoral artery it was observed to be obstructed by a clot. We were immediately concerned that he might have clotted systemically. Fortunately, this was not the case and the clot in the femoral artery was the only one noted at any time during blood washout or subsequent cryoprotective perfusion. It had a “retracted” appearance indicating that it had probably occurred during the agonal period when his peripheral circulation was being shut down to conserve blood flow to the brain and core organs.

Blood washout was terminated at 11:58 AM at a venous pH of 7.80. This is the first time we’ve ever reached such a desirably high terminal pH and this was achieved, we believe, as a result of the addition of a modest amount of potassium phosphate to the perfusate to augment the organic HEPES buffer which we have used alone in the past.

We also think it possible that the addition of phosphate and ribose to the flush perfusate resulted in better metabolic support to the muscles (and presumably neurons and other body cells) during the subsequent cold ischemia of air transport. When the patient arrived at the facility rigor mortis was present only in the leg that had been unperfused as a result of being used for the femoral cut-down (since Dr. Nalley had elected for neurosuspension, no effort was made to perfuse the limb supplied by vessels used to carry out the blood washout). It is not possible to be certain that the absence of rigor was a result of these changes in perfusate composition, since the use of the Pizer tank almost certainly resulted in substantial protection of muscle energy reserves by facilitating more rapid cooling than has been achievable in the past.

Another change in procedure was the use of 20 liters of Dextran40- containing perfusate for initial washout, which was then “chased” with 10 liters of base perfusate in which hydroxyethyl starch (HES) was substituted as the colloid. Our experience with two previous patients had indicated that Dextran 40-containing flush solutions resulted in more complete blood washout and considerably less cold agglutination than we have previously observed. Unfortunately, Dextran 40 is undesirable to use for cryoprotective perfusion because it tends to leak from the capillary bed and it is somewhat toxic to the endothelial cells which line the capillaries. This latter effect is a consideration of some import when the exposure time of the capillaries to the agent will be many hours, as it is during air transport of patients like Dr. Nalley. It was for this reason that its concentration was greatly reduced by flushing the circulatory system with 10 liters of base perfusate containing HES.

From the beginning of the transport procedure, continuing through blood washout and preparation for shipping, Dr. Nalley’s children, Jim, Gene Jr., Ray, and Diane were present and assisted every step of the way. Jim started manual CPR after legal death was pronounced until we could couple the patient to the heart-lung resuscitator. CPR was continued while transporting Dr. Nalley to the mortuary and setting up the circuit for blood washout. Cindy scrubbed in and assisted Jerry and me with the cutdown and blood washout.

Following the completion of blood washout, Dr. Nalley was prepared for air shipment by being placed in an insulated chest and completely packed in ice in Zip-Loc bags. We were fortunate that blood washout was completed in time to catch a direct flight leaving Detroit International Airport at around 3:00 PM and arriving at Los Angeles International at about 7:00 PM. Jim and Cindy had decided to accompany Dr. Nalley on the flight and, emotional state permitting, participate in the rest of the cryonic suspension procedure.

All of us at Alcor had real misgivings about the latter idea, but we also felt very strongly that it was important for purposes of both reassurance and accountability to let the family be present if they could handle it. As it turned out, not only did Jim and Cindy hold up well emotionally, they were two of the most useful people around.

Cryoprotective Perfusion

Dr. Nalley arrived at the facility at about 10:00 PM and by 10:30 PM his rectal temperature had been measured at 2.0°C. Surgery was begun at 1:11 AM on the morning of the 22nd and perfusion was begun at 3:22 AM.

Keith Henson records Dr. Nalley’s arrival temperature as it is measured by Mike Darwin. Photo by Elleda Wilson.

Immediately after arrival in the facility, the transport container holding Dr. Nalley was opened in preparation for his transfer to the operating table. He was packed in ice from head to toe for air shipment from Detroit to Riverside. Photo by Elleda Wilson.

Alcor biochemist Hugh Hixon completes final calculations on glycerol concentration near the end of perfusate preparation. Photo by Elleda Wilson.

Dr. Nalley is positioned on the operating table. Photo by Elleda Wilson.

Final preparations to the heart-lung machine are made prior to the start of perfusion. Photo by Elleda Wilson.

Jim Nalley supports Jerry Leaf’s back as he prepares to open the dura mater covering the patient’s brain. Photo by Elleda Wilson.

Blood washout of the brain, as evaluated though a 10mm burr hole over the parietal cortex, was excellent. The pial vessels on the cerebral cortex surface were free of blood, as were the tissues of the chest and head which were incised to gain access for vascular cannulation and opening of the burr hole (hematocrit at the end of blood washout was unreadable). The use of Dextran-40-containing flush seem ed to provide better blood wash out than has been observed with the use of HES flushes, extending the experience we have had with the last few suspension patients treated under similar circumstances.

The burr hole was opened prior to cryoprotective perfusion and the cerebral cortex was observed to be free of both blood and edema. Cryoprotective perfusion with glycerol in our sucrose-HEPES (SHP-1) perfusate began uneventfully. Approximately 40 minutes after the start of glycerol perfusion, a modest increase in brain volume was observed indicative of developing cerebral edema. We had anticipated cerebral edema secondary to ischemic injury as a potential problem because of the long agonal period and poor circulation during CPR. Our initial strategy in controlling cerebral edema consisted of increasing the slope of the glycerolization ramp from a rate of approximately 20mM per minute to 40mM/min. This was effective for awhile, but it soon became necessary to switch from continuous perfusion to pulsatile flow (with a ramp rate around 25mM/min.) in order to control edema.

Pulsatile flow was not effective in reducing the degree of edema, but it did stop its progression. The surface of the cerebral cortex was thus bulging into the burr hole only about 1-2 mm at the conclusion of perfusion.

Checking For Flow